Who was Jessie? Acquaintance? Confidante? Love interest?

No-one knows – nearly eighty years after a WW2 soldier and the mononymous ‘Jessie’ exchanged letters, she remains just that. A Christian name in a war diary.

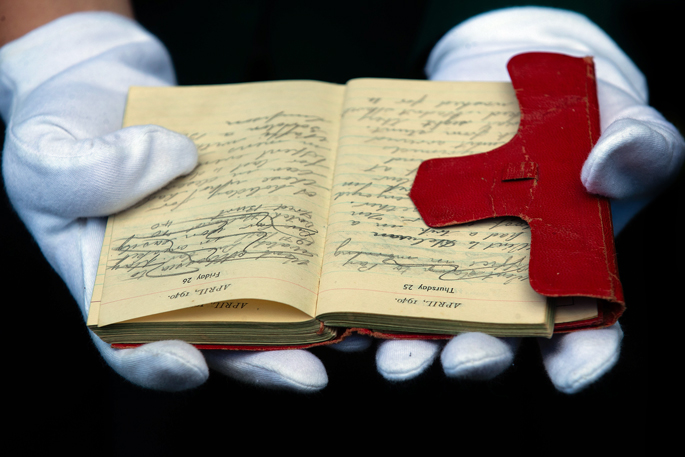

“It’s beautiful,” says Katikati Museum volunteer Pauline McCowan who transcribed a whole year of the soldier’s 1940 war diary. “He was writing to this mystery woman and we still don’t know who she is.”

Sunday, June 2, 1940: “Very hot. Wrote a letter to Jessie all afternoon.”

But tantalisingly, we don’t know what he wrote.

The soldier wrote often, in pencil and strong, flowing, cursive. Said something of the man’s style. “He would often mention writing home to Jessie and his mother.” So Pauline tallied it up. “Jesse got many more letters than anyone else.”

Sunday, January 9, 1940: “Wrote to Jessie. Posted air mail.”

And so on, every few days. “But no, no clues as to who she was,” says Pauline. “We don’t even know if she was in New Zealand. Neither does his family. Not to this day.”

Sunday, May 12, 1940: “Wrote to Jessie between air raids.” There was obviously a chemistry, but was there passion, romance. The emotionally detached diary entries offers the reader nothing.

Venture down Katikati’s Main Road to the War Memorial Hall and we learn more of the lovelorn soldier.

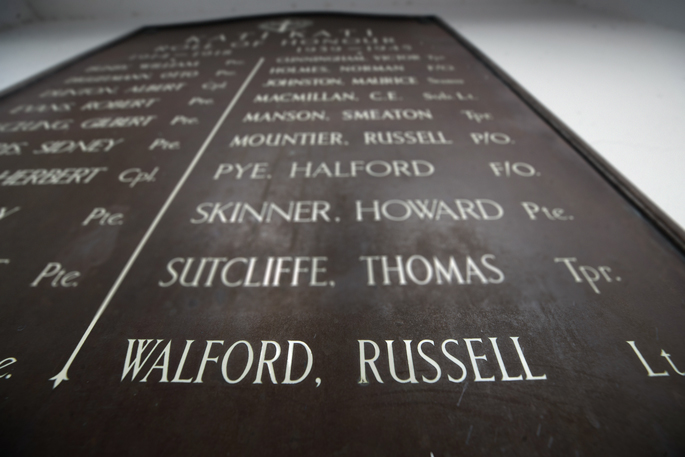

In Memoriam – the plaque at the Katikati War Memorial Hall.

In Memoriam – the plaque at the Katikati War Memorial Hall.

Cunningham, Victor; Holmes, Norman; Johnston, Maurice. All sons of Katikati, fallen WW2 heroes, names on a plaque. Manson, Smeaton; Marsh, Allan H.; Mountier, Russell.

Aah, there he is. The letter writer.

Walford, Russell Freeland, Lt or Lieutenant.

The last of 12 Katikati names on the WW2 memorial panel. Lieutenant Russell Walford, service number 1024, 20th Armoured Regiment. Died December 16, 1943, in the battle for Orsogna during the Italian campaign. Just 29-years-old.

His tank had been knocked out while retreating from a position that had come under German fire. It’s understood he was lying with other injured in a church yard when they were again caught in a maelstrom of German tank fire, anti-tank gun fire and flame throwers.

One surviving tank gunner recalled it being the worst experience of his life. “Thirteen tanks went in, nine were shot up, several of the boys killed.” It was his, the gunner’s, first taste of action. ”I wasn’t afraid so much, but sad. Fellows I’d been talking to a week earlier, you know, stiff and dead. Never see home again.”

.jpg) Russell Walford’s 1940 diary.

Russell Walford’s 1940 diary.

Lieutenant Russell Walford now lies in a groomed plot, 1X.D.20, at the Sangro River War Cemetery in Chieti, central southern Italy. The son of Katikati is now a son of Italy too.

“He was a nice man,” concludes Pauline McCowan, the Katikati Museum volunteer. “He talked about having a good time with his mates. He enjoyed sing-songs, he loved dancing, he was respectful, called his parents ‘mother’ and ‘father’. He was also a very good looking man.” And by the time she finished transcribing his diary Pauline she felt completely in love with him.

“It was such a beautiful and privileged task. He just sounded like a really decent bloke.”

Friday, October 11: “Received parcel of socks and hankies from Jessie. Just what I wanted.”

Much of the diary is the daily mundanities - manoeuvres in the desert, a dental appointment, a debilitating bout of “gippo tummy” and a more sobering moment – a funeral for the “first man of the regiment to pass away”.

Thursday, December 12: “Train load of Italians (prisoners) passing throu (sic).Poor looking lot. Received air mail from Jessie.”

No mention of the horror, the blood and gore stories from the front line. Although he did write excitedly about seeing his first air raid over Cairo.

Saturday, June 12: “Anti—aircraft guns opened up. Vivid flashes through the sky. Fair bit of noise while it lasted.” But the very next day he went to the movies to see Gracie Fields in ‘Shipyard Sally’, and then the following day surfing and “great fun” catching dangerous and venomous Death Adder snakes, large lizards and spiders with their bayonets.

We’re back on Katikati’s Main Street and it’s just gone midday. The clock tower right outside the Katikati War Memorial Hall tells reads 12.02 to be exact. I check it against my phone – it’s bang on time. Excellent! Lieutenant Russell Freeland Walford, 20th Armoured Division, would approve. The clock raised in his honour at the grand cost to his family of £100 is ticking with military precision.

But it’s not just a clock, not just a monument – it’s a symbol of time, mortality and the passage of life. The passage of one specific and special life, lest we forget Russell Freeland Walford.

The soldier’s diary and medals are now in the keeping of Western Bay Museum in Katikati.

.jpg) The soldier who didn’t come home: Lieutenant Russell Freeland Walford.

The soldier who didn’t come home: Lieutenant Russell Freeland Walford.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.