Walking into Kelcy Taratoa's atrium installation at Tauranga Art Gallery, you realise that there really are no boundaries to art, design and colour.

On one wall, a strong kowhai yellow beckons. Facing it are muted greys and blues, and linking both is a high wall woven with red shapes and designs bringing to mind traditional patterns I've seen on maraes.

The wharenui reference is by plan. Kelcy is drawing us into a communal place to meet and be, pulling us from the past and into his view of the future. And it's light, bright and hopeful.

I had wondered who this descendent of Henare Taratoa would be, and how clouded or clear would be his eye and heart, given what I thought would be historical family suffering from the past, and the loss of leaders and ancestors from years gone by. Henare, a notable missionary, teacher and war leader of Maori descent was killed in the Battle of Te Ranga.

I expected to find strong and perhaps confronting visual statements of identity, which I would then grapple with and seek to understand. Instead I find myself immersed in an open, gracious and warm welcome.

On the walls, tukutuku patterns reveal themselves. They traditionally make up the interior architecture of the wharenui, and are a distinctive art form and latticework used to decorate meeting houses with woven panels. Somehow they are weaving themselves into the architecture of the gallery.

It's a delight to meet the artist himself. There's a clarity of eye, a soft smile, and a gentle spirit behind the man.

'I've been disassembling these patterns into their basic geometric shapes and reworking the patterns,” says Kelcy.

There's an evolving thread of identity here, linking the past to the contemporary.

'I've been very much interested in the impact of history on the individual, on one's social situation and how one forms an identity from this.

'Doing an important body of work on this has allowed me to go back and look at imperialism, colonialism, and the assimilation of Maori into the new culture. How that impacted on Maori who lived as a collective very much connected to the land, with towns and cities being built around them. New Zealand was transitioning into a country that was trying to find its own voice in the modern world.”

'My dad grew up in a time where Maori wasn't spoken at school. My grandparents all spoke Maori, but to ensure that my father and his siblings could engage in the new world they focussed their attention on English. It's created some challenges for many Maori moving forward – where do we sit? Where's our place? In the grey space as I call it, we're trying to straddle two worlds.”

The joy about viewing Kelcy's work though is that there is a clarity and no confusion, despite trying to artistically articulate the challenges of constructing an identity out of the ruins of history.

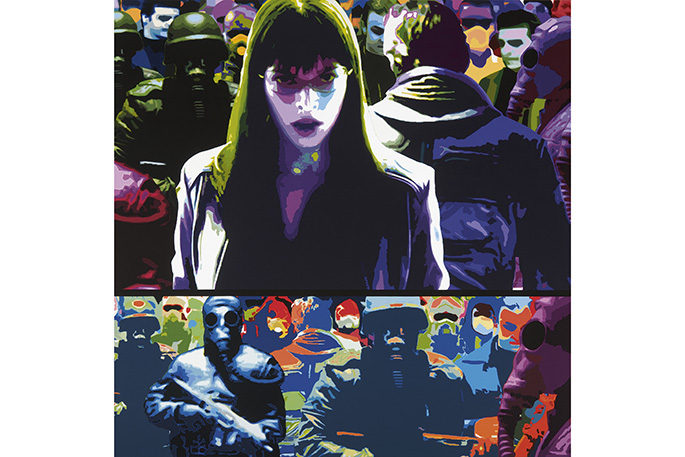

Other bodies of his work explore the notion of the hero and the existential questions around that. What does it mean to be? How do I know I exist? How do I arrive at meaning for my life? How does my life mean something?

Culture can provide a role for us and give us purpose.

'If we're culturally dislocated and alienated it poses some additional challenges, but even still, there are belief systems that people have constructed because of this challenge of arriving at meaning.”

Upstairs is a mid-career show of Kelcy's paintings, more than 30 works on loan from NZ and overseas collectors. I find that Kelcy is curious to see how they capture moments of the past, his past.

'They take me back in time. They capture a moment of yourself and where you were at in terms of your thinking and your abilities. You realise you were quite a different person then.”

Viewing them, you're drawn to the journey through his own heart and mind as he has explored cultural identity, drawing links from the past and weaving them with contemporary themes.

Kelcy explains two moments he experiences during the painting process.

'One distinct moment is in the studio when you complete the work and you stand back and think about ‘is this what I envisioned?' and ‘am I happy for it to leave the studio?' And the next moment is the moment when it's placed in a gallery. I ask to be alone in the space and have my final moment with it. And then it's gone.

'It's like being a parent. I have my time making it, with the understanding that it then has a life of its own, just like our tamariki do.”

Kelcy is looking forward to using the retrospective exhibition as a platform for education.

'My art work is in the secondary school's art design curriculum and I'm often asked by school teachers if I have any time, could I come and do some work with the students. And of course I don't have much time.

'I thought this type of project would be great as a resource to bring schools in to the art gallery where I can work directly with them, but also create an educational resource, a publication very much connected to the retrospective and make it available for educators to use in the classroom.”

Kelcy Taratoa's exhibition at Tauranga Art Gallery runs until March 1, 2020.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.